C.C.M. Rindt, M. Gaeini, S.Lan, D.M.J. Smeulders

Eindhoven University of Technology, PO Box 513, 5600 MB Eindhoven, The Netherlands

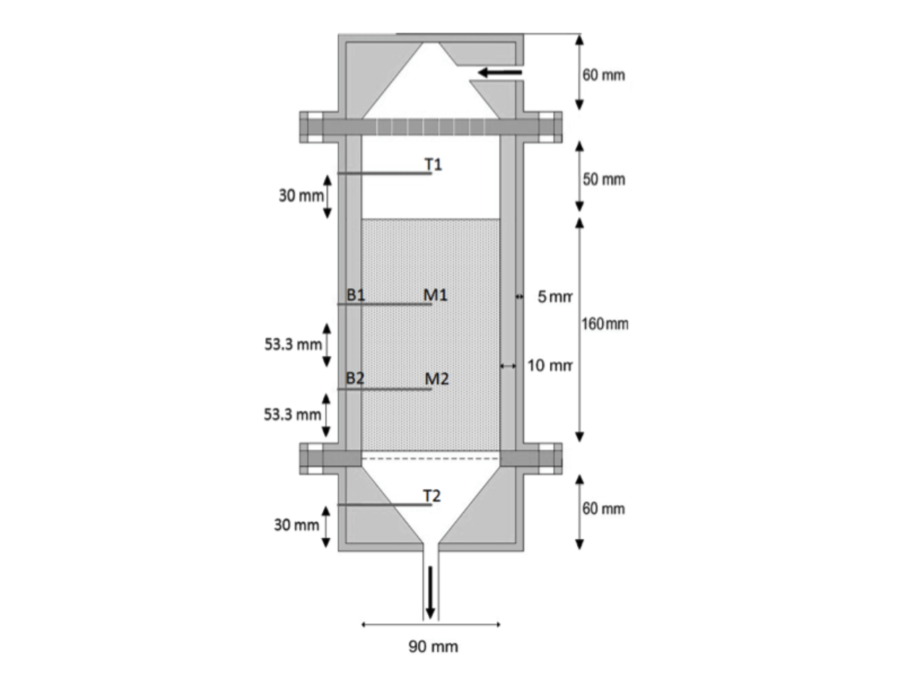

In summer, the sun provides more heat than needed to warm residential houses while in winter the heat demand cannot be met by solar energy supply. A solution is to store excess solar energy in a thermal ‘battery’ which can be discharged to meet the residential heat demand in winter. A reliable method for seasonal solar heat storage is by means of thermochemical materials (TCMs). The process is based on a reversible adsorption-desorption reaction, which is exothermic in hydration and endothermic in dehydration (Shigeishi et al. 1979, Zondag et al. 2013). In this research, a lab-scale prototype thermochemical heat storage system was tested (see Fig. 1). In the experimental setup, air enters a reactor vessel filled with zeolite 13X. The air can be hot and dry to charge the thermal battery, or cold and moist for discharge. In the latter case, the idea is that the thermal battery generates heat to warm up the air by means of an exothermic adsorption of water to the zeolite (hydration of zeolite and dehydration of the moist air). The temperature profile is measured as a function of time along the flow direction. Input and output temperatures, pressures and humidity are measured.

A thermal model is developed for the packed bed during the hydration of the zeolite (Gaeini et al. 2014). The model includes mass and heat transfer in the gas, the packed bed and the reactor wall, as well as the adsorption reaction of water vapor on the zeolite. Equilibrium constants are modeled as a

function of temperature. By comparing the temperatures of the experimental investigation with the results of the numerical simulation model, the kinetic parameters for the adsorption in non-isothermal and non-adiabatic conditions are found.

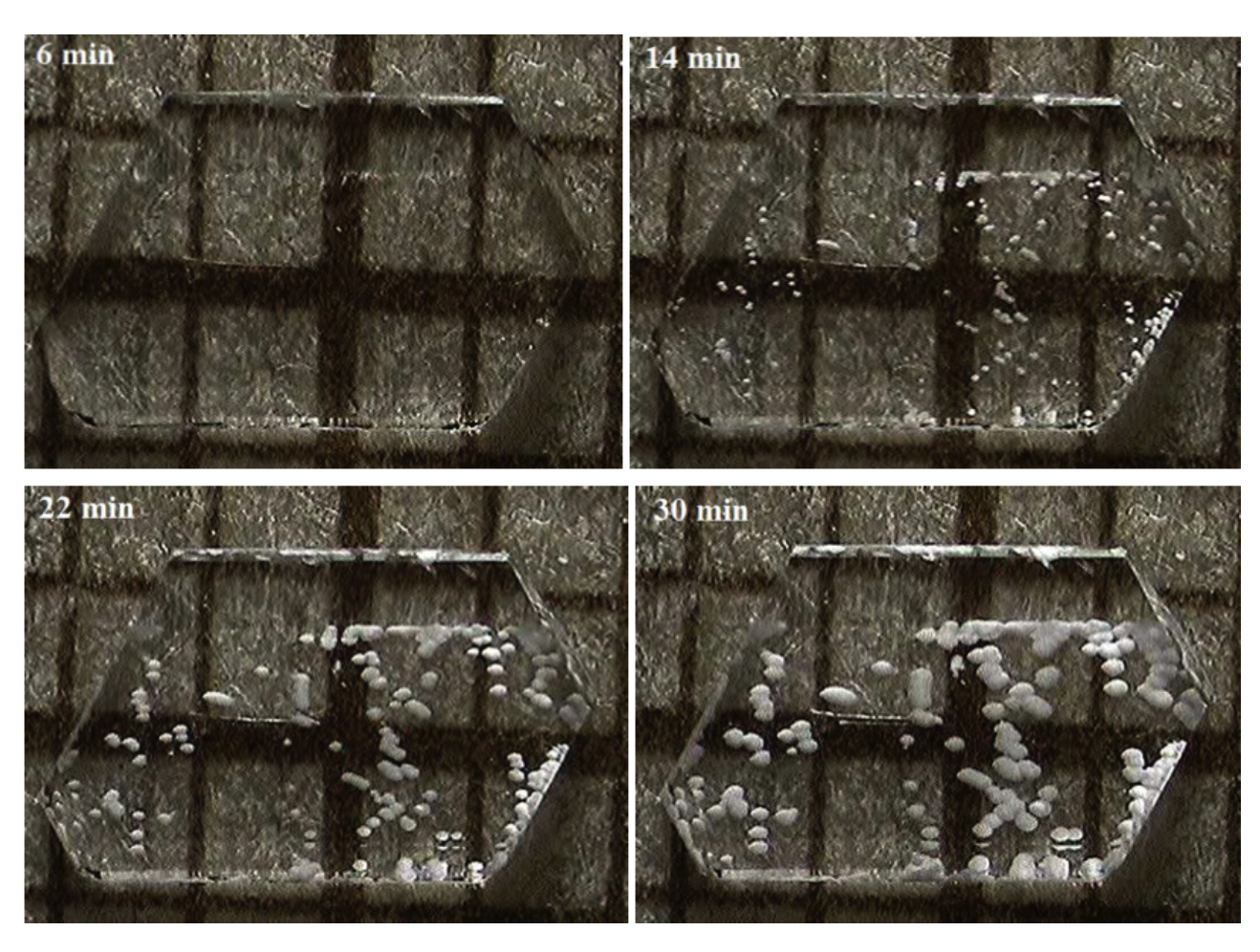

We also investigate the dehydration reaction on the smaller scale by means of optical microscopy. Following Brown et al. (1992), we now use Li2SO4.H2O as heat storage material. The dehydration reaction is found to proceed through formation and growth of nuclei over time (see Fig.2).

Crystals were embedded at room temperature in a liquid resin called EpoFix resin, which hardened within 10 hours. An important feature of this resin is that it will maintain its transparency at 130 oC up to 5 hours, which ensures that the phase change is visible during the entire reaction. Encapsulated crystals were polished using abrasive paper. The resin layer was polished up to a thickness of ~ 1 mm, which is thick enough to impede gaseous product release. There are two reasons to make the resin layer this thin. One is that the resin is a poor thermal conductor. In order to achieve a certain reaction temperature, the resin has to be heated up to a higher temperature if the layer would be too thick. Unfortunately, the transparency diminishes rapidly as the temperature increases. The other reason is that the reaction temperature profile should be close to the resin temperature profile to establish the correct reaction kinetics (Koga and Tanaka 1989). Figure 2 shows a typical sequence of the nucleation and nuclei growth processes on the surface of a single crystal. The mesh on the background provides information on the length scale (grid size 1mm). The reaction proceeds by the conversion of the transparent phase to the opaque white phase indicating the formation of nuclei and nuclei growth. Imperfections of a crystal are potential nucleation sites. Hence, more nuclei are observed at the grain boundaries such as edges and cracks. Apparently, in this case the growth process was dominant over nucleation. It was found that the number of nuclei is more or less constant.

References

- Brown, M.E., Galwey, A.K., Li Wan Po, A., ‘Reliability of kinetic measurements for the thermal dehydration of lithium sulphate monohydrate: Part 1. Isothermal measurements of pressure of evolved water vapour,’ Thermochimica Acta, 203 (1992), 221-240.

- Gaeini, M., Zondag, H.A., Rindt, C.C.M., ‘Non-isothermal kinetics of zeolite water vapor adsorption into a packed bed lab scale thermochemical reactor.’ Proc. 15th Int. Heat Transfer Conference, IHTC-15, August 10-15 (2014), Kyoto, Japan.

- Koga, N. and Tanaka, H, ‘Kinetics and mechanisms of the thermal dehydration of Li2SO4.H2O,’ J. Phys. Chem., 93 (1989), 7793-7798.

- Shigeishi, R. A., Langford, C. H., and Hollebone, B. R., ‘Solar energy storage using chemical potential changes associated with drying of zeolites,’ Solar Energy, 23 (1979), 489-495.

-

Zondag, H., Kikkert, B., Smeding, S., de Boer, R., Bakker, M. ‘Prototype thermochemical heat storage with open reactor system,’ Applied Energy 109 (2013), 360-365.

Source: http://upcommons.upc.edu

![Ο Περιφερειάρχης Αν. Μακεδονίας & Θράκης, Α. Γιαννακίδης για ζεόλιθο [Video]](https://zeolife.gr/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/o-perifereiarhis-anatolikis-makedonias-kai-thrakis-gia-ton-zeolitho.jpg)